Mental health: an individual's problem or a societal issue?

Mental health, anti-poverty and youth advocate Esther Whitehead, a Queenstown local, takes a look at why living in paradise doesn't mean we're happy...

In a Crux article dated May 19, 2018, journalist Eileen Goodwin explored the challenges of mental health support in Queenstown.

John MacDonald, chairperson of the Southern District Health Board’s (SDHB) mental health and addictions network, and a Queenstown Lakes District Councillor, said he was frustrated “with a hospital rebuild in Dunedin and a hospital refurbishment in Queenstown, it’s the ideal time to rethink mental health services for the whole region, but that’s not happening”.

Esther Whitehead: To ask why we're not coping creates tension, but to ignore it is far more uncomfortable.

Queenstown is not experiencing these problems in isolation though.

Last year, the New Zealand Herald (1) reported that, in 2016, almost 300,000 Kiwis were prescribed anti-depressants - one in 10 adults and a whopping 14,000 children (under 18 year olds). These numbers have since grown and I have to ask, why we are not coping?

To ask the question “Why?” certainly creates tension, but to ignore it is far more uncomfortable. The suicide rates in New Zealand are distressing - one suicide is too many, 606 per year is deeply tragic (2).

Why are so many Kiwis, of all ages, having difficulty coping? Why are so many in today’s world so lost and battling mental health issues?

Well, there is widespread recognition of the loss of human contact and connectivity, and the effect this has on individuals. It’s possible that it’s far more common than many realise. I’m no doctor, counsellor or psychologist, but it seems that it’s not us as individuals who have the issues - it’s a far deeper societal issue.

A commonality across many western countries is the increased rates of diagnosed neural disorders and mental health issues, such as ADHD, autism, anxiety, depression and the list goes on. Take ADHD - it has literally swept across the United States in epidemic proportions. Can we really be seeing a global epidemic in neural disorders? What if ADHD or depression were not seen as a disorder of the individual’s brain?

The way a person thinks and responds to stimuli is representative and reflective of the world they live in. The fact that, societally, we do not recognise that a person is integral to their surroundings, means that anyone who doesn’t “fit” the current system/culture is deemed “different”, “sick” or “invalid” in one way or another. Our children who think differently are prescribed drugs so that they can fit the system.

The Kingdom of Bhutan made the connection between societal and environmental health to mental wellbeing back in the 1970s, with the belief that GDP (Gross Domestic Product) is not the only, or best, measure of a nation’s success.

Is there not something terribly wrong with the world when we’re routinely observing global woes through the safety of impassive indifference?

The recently celebrated Australian comedian Hannah Gadsby struggled with understanding her differences (recently diagnosed with Autism) and grew up feeling marginalised (possibly also because until the 1970s homosexuality was deemed a disorder by the IDS!), but says she now understands that “I’m not broken, the world is”. If you haven’t seen her globally famed “Nanette” on Netflix, it’s a must watch!

Mental health referrals in the Southern Lakes have increased in recent years.

It seems no coincidence that we measure the success of societies by their citizens’ collective ability to earn money and consume stuff and that we are not measuring people’s ability to connect to meaningful experiences.

Let’s take a moment to ponder how GDP measures our collective wellbeing. The GDP of a country does not take into account how the wealth is spread - we know the wealth equity gap is alive and well. Secondly, GDP increases when a country is highly extraction-focused and highly carbon-dependent, such as extracting oil from the earth, or logging trees etc. For example, imagine if Brazil logged the entire Amazon Rainforest - its GDP would increase hugely and it would consequently be “rich” for many years. Its political leaders would want credit for creating wealth. When it’s described this glibly, we can understand that GDP is not a catch-all index, whether by design, or short-sightedness.

If neural epidemics are the disease of our time, what then is the antidote? Counselling and medication are surely the ambulances at the bottom of the cliff.

If we were to view the prosperity of our people differently, we may begin to discover that the antidote is meaningful connection to place and people. With cycles of collapsing global financial systems and wide-scale environmental destruction, we are shortsighted if we do not have the courage to recognise that we are part of a greater ecosystem that has ecological limits.

We are wilfully ignorant of our own and others’ “displacement” in society. We choose to turn a blind eye, or to point the finger at the inability of others to “fit” the system. Perhaps many people nowadays find that the world around them no longer fits their values - it’s depersonalised, unfamiliar and as though “something is off”. It’s nauseating when we can’t recognise collective neural disease as a consequence of such a narrow measure of success.

The Kingdom of Bhutan has Gross Domestic Happiness, an index which sounds fluffy and contrived at face value but, when we dive deeper, we find that its intents and mechanisms protect people and nature’s wellbeing as the standard from which everything else is formed.

Our progressive coalition government offers some optimism, as does our regional and local authorities - with divestment from fossil fuels, commitments to better living standards and social health at a national level, our regional commitment to re-introducing social wellbeing measures, and our local council is surveying our quality of life very soon. We’re tracking in the right direction for sustained wellbeing. This is a refreshingly stark contrast to what’s happening in much of Australia’s Queensland, where I’m writing from.

Kiwis are renowned for their friendliness, but let’s cut the small talk, break taboos and talk about stuff that matters. Take the survey, listen to others, ask for help, advocate for wide-scale wellbeing.

When we have choices, we can hope for a better future and, when we can access appropriate support, we can seek help when it’s most needed. We are all inextricably linked - when we break it, we become undone.

Esther Whitehead is a volunteer in our community, Managing Trustee of the Dyslexia Foundation of NZ and has worked closely with Judge Andrew Becroft, on neuro-diversity, poverty and youth justice.

Read: Eileen Goodwin's earlier mental health story on Crux.

1. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=11870484

2. https://www.nzherald.co.nz/lifestyle/news/article.cfm?c_id=6&objectid=11914490

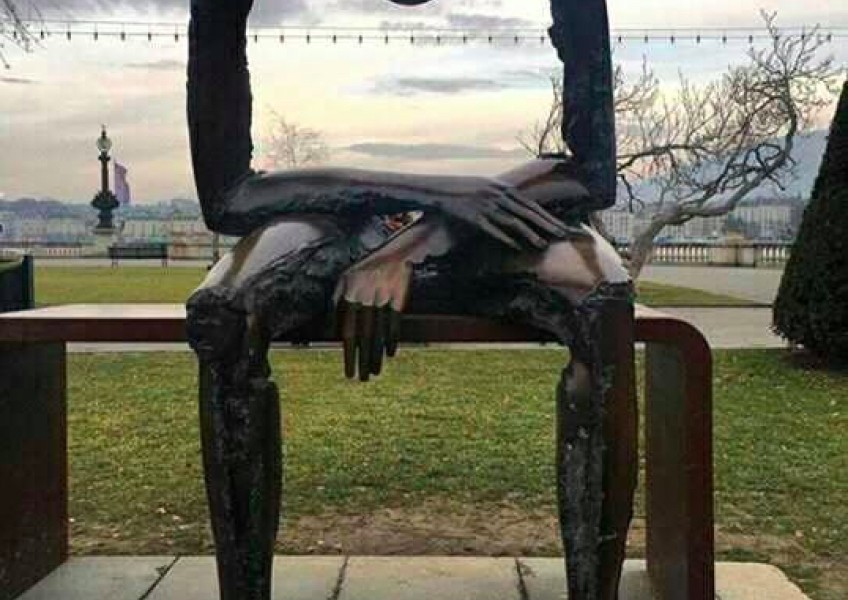

Main image: Artwork in Geneva entitled Melancolie, created by Albert György.