Our housing problem explained - economist calls for action, not 'more stalling and studies'

Reader contribution: Ralph Hanan is a former senior World Bank economist who lives in Queenstown. Mr Hanan wrote one of the most popular and intelligent Crux articles ever published, three years ago in 2020, comparing aspects of Queenstown's spectacular growth to a dangerous Ponzi scheme that future generations would have to suffer.

In recent months I’ve come across several reports that have discussed the unavailability of affordable housing in our district, especially in the Queenstown area. The following four deserve mention.

First, Deputy Mayor Quentin Smith was reported by RNZ as saying Queenstown’s housing crisis was due to very high demand for short-term tourist accommodation combined with a relatively low-wage economy centred on tourism. Elsewhere he has described the situation as complex.

Ralph Hanan - a former senior economist with the World Bank - and a Queenstown resident.

Second, the Minister of Housing, Megan Woods, when visiting Queenstown in mid-April, was reported as saying our housing crisis has been decades in the making. She said she appreciated being informed on the issues but there was no quick fix the Government could deliver.

Third, Queenstown Lakes District Council chief executive Mike Theelen was reported by the Mountain Scene as saying building more houses was not the answer to Queenstown’s acute rental housing crisis. He noted that demand for our housing has always come from beyond the Queenstown Lakes as people from elsewhere in New Zealand and overseas think it’s a good place for a holiday home or an investment. He referred to a recent report by economist Benje Patterson, which informed that there were more than 1,000 new homes consented than were needed last year. In other words, we are not short of homes for renting. Their availability, however, is another matter.

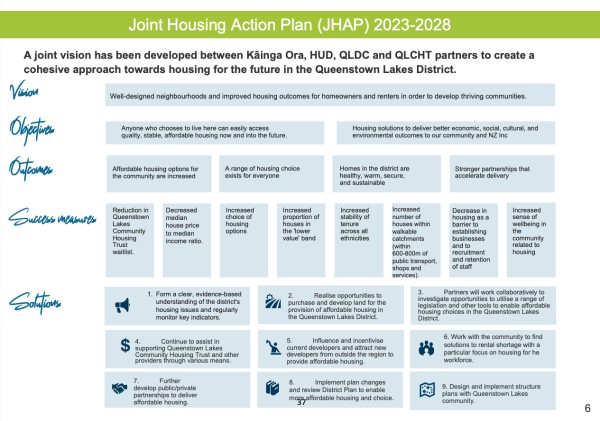

Fourth, the QLDC released its draft Joint Housing Action Plan 2023-28. I don’t intend to review this housing plan here, save to mention its key objective: “Anyone who chooses to live here can easily access quality, stable, affordable housing now and into the future (my italics)." This contrasts with the QLDC’s 2002 report “Tomorrow’s Queenstown”, whose community priorities were: (a) Priority issue number one - managing population growth; and (b) Priority issue number three - managing visitor growth.

What, we may ask, has led the QLDC to conclude that our community’s priorities have changed so fundamentally when the pressures of population and tourism growth and their impact on our infrastructure and social fabric are more acute now than they were before?

Not least, the draft plan comments, “It is important to note that there is enough zoned land in the district to provide for the long-term growth” (of housing). Why then does the plan argue for zoning more land to accommodate more urban housing?

An underlying issue for many in our community is, what are the limits to our growth? At what point do we say “Enough, we are full”?

The QLDC's draft Joint Housing Action Plan doesn't allow for 'enough is enough' when it comes to population growth, economist Ralph Hanan argues.

These four reports pose the question: what should be done about the housing problem? And by whom? Some locals with housing difficulties have been saying the Government must do something. Others are saying the QLDC must do something. But what is the something?

The costs of housing in the Queenstown area – acquisition and rents - have escalated to unaffordable levels. Some employees are living in cars or tents, or hot-bedding to share the high rental costs of a room. The scarcity of rentals has pressured rents to levels beyond the means of many workers and families. Health concerns threaten as winter approaches.

Some workers are choosing to leave Queenstown for elsewhere in New Zealand. Others may wish to leave but their work visas limit their employment to Queenstown only.

We have a paradox. Local businesses – mostly hospitality and tourism-related – are short of workers. They have complained that the Government’s constraints on immigration are limiting the availability of workers. Restaurants have reduced their hours and some are closed one or two days a week due to a lack of staff. Others have closed altogether. Yet our existing workers have insufficient accommodation. If the Government were to relax its immigration constraints, the influx of additional workers would make our housing crisis worse.

The conversion by property owners of their units from long-term rentals to Airbnbs is contributing to the unavailability of housing. Owners receive more income from Airbnbs than from long-term rentals so the conversions are understandable.

As a new technology, Airbnb falls in the rubric of creative disruption, disrupting our market for long-term rentals. Like other innovative technologies, it is here to stay. Legal challenges, like ‘Ban Airbnbs’ or to limit their availability, are unlikely to be successful. We must learn to adapt.

The Queenstown Lakes Community Housing Trust, according to its 2022 Annual Report, had assisted 243 households under its various housing programs. The trust’s goal is to assist 1,000 eligible low to moderate-income households into affordable homes by 2038. As of now, many households – nearly 900 - are on its waiting list for housing, a number that’s likely to grow and far exceeds the trust’s financial and administrative capability.

So, what’s wrong?

Traditionally, tourism in Queenstown has been a low-productivity, low-wage activity. It is labour-intensive with limited scope for investment in technologies or scale to improve productivity and wages. The generous supply of labour from young people coming to Queenstown for the experience has contributed to keeping wages low. Local businesses, moreover, have thrived on these low wages, which have detracted from capital deepening to diversify our economy (improving the ratio of capital to labour) and thereby to increase the value-added (and wages) per worker.

At the same time, Queenstown has become recognised world-wide as a tourism mecca. Its outstanding natural features and desirable way of life lead many to want a slice of our paradise. The demand for housing, from within New Zealand and overseas, pushes house prices beyond levels most Kiwis can afford and rents beyond the capability of many low and middle-income earners.

Contributing to the complexity is our limited topography and deficient infrastructure. We cannot expect to build our way out of what effectively is global demand. This is the point made by Mr Theelen.

Is building our way out of our housing crisis a solution?

In a real sense, we have become victims of our success. Marketing strategies by Tourism New Zealand with its moniker ‘100% Pure New Zealand’ and by our Destination Queenstown have been successful in driving this success. Queenstown is now an internationally-recognised brand.

There are sound arguments for increasing the availability of affordable housing in the Whakatipu. We need teachers, police, nurses, and other professionals, as well as wage and salaried employees for our hospitality, tourism, and other services. But being such a sought-after destination, the prices of our housing are unlikely to recede. Much of our new housing will continue to be snapped up by well-heeled buyers who bring their cash from elsewhere.

One recommendation in the QLDC’s draft housing report is to build more houses to solve the unavailability and unaffordability problem. The additional supply – supposedly - would satisfy the demand and lower the cost of housing. Implicit in this thinking is that demand is a constant – it is a fixed amount - and by increasing the supply prices will come down. That’s a fallacy. As noted, demand is huge and it’s dynamic. In the Queenstown area it will continue to outpace our efforts to increase supply at affordable prices. Therefore, additional supply is unlikely to make a dent in our crisis of unaffordability.

Take some existing developments. The increase in supply at Jacks Point was expected to make housing available, and affordable. Similarly, Lake Hayes Estate, Shotover Country, Bridesdale, and now Hanley’s Farm where the more than 1,500 residential lots are built on or under contract. It is naïve to think that further residential developments will satisfy the demand for more housing.

Consider, for example, the proposed development of around 2,400 houses on the north side of the Ladies Mile. It has become a community flash point for the merits, or otherwise, of more urban zoning in that location. The development is emblematic of spatial conflicts in integrated urban planning, as local authorities try to weigh or strike a balance between the private gain of developers and the economic, social, and environmental costs to the community.

More houses are adding pressures on our public infrastructure, most noticeably our roads. The congestion along the Ladies Mile and at the BP roundabout is becoming worse. Being stuck in traffic incurs economic, social, and environmental costs. Time is money. Commercial transport and trades people are delayed in reaching their destinations. The additional costs are passed on to our businesses and consumers, adding to our cost of living. Residents become frustrated with the additional time it takes to get to work or appointments, or wherever else they are going. Not to mention the impact of increased vehicle emissions on our air quality.

Referring again to the Ladies Mile development, we may ask whether the economic, social, and environmental costs to our community will outweigh the benefits. There’s no question that these costs are considerable. The benefits to our community, however, are more debatable. The evidence suggests that the development is unlikely to reign in the high costs of housing, and therefore will do little to alleviate the shortage of affordable rentals.

At the very least, our council should insist that the necessary public infrastructure, e.g. widening Highway 6, precedes a new housing development, not the other way round. Though this sequence should be self-evident, the QLDC appears not to appreciate this, or it is dancing to some other tune.

A congested State Highway 6: 'At the very least, our council should insist that the necessary public infrastructure, e.g. widening Highway 6, precedes a new housing development, not the other way round': Ralph Hanan.

Further on the Ladies Mile development. The QLDC’s acting planning and development manager was reported by RNZ as saying, “Housing lies at the heart of creating secure, connected and caring communities, creating jobs and a diverse economy.” The comment was clearly in support of the development proceeding.

While new housing does create jobs in its construction, it is not of itself a productive investment. Rather, it is a social good, providing shelter. Unlike other investments - businesses, stocks, and bonds - it does not earn the owner-occupier a stream of dividends or interest. It does create jobs for maintenance, and for insurance and mortgage providers (and increased rates and income for the QLDC), but little else. We may ask whether the scarce capital should be deployed elsewhere, helping to diversify our economy into high-paying jobs on a sustained basis.

Regarding the quoted creation of a diverse economy, we need only consider whether the large housing developments mentioned above have diversified our economy. The reasoning is spurious, like a shell game, serving to mislead the community as to the merits of the Ladies Mile development. The QLDC should present the benefits and costs fairly, covering both sides of the argument, and then consult effectively with the community and respond to its wishes. That is the essence of a viable local democracy, something that unfortunately has diminished in recent years.

An inconvenient truth is people are not compelled to live in Queenstown. It is a choice. While the Government’s 100% Pure New Zealand campaign has been successful in promoting tourism, this very success is severely impacting our housing and our community’s wellbeing. Our Lakes District bats above its weight in contributing a share of our local economy to Wellington, particularly with foreign exchange but also through GST and tax receipts. It follows that the Government should share with our community the costs of mitigating our housing crisis.

So what are our options - short-term, medium-term, and long-term?

In the short term, QLDC’s draft Housing Plan recommends an investigation into the obstacles for landlords to rent their properties for long-term accommodation. Why the need for an investigation, another study? The National Party has promised to rescind the recently implemented tenancy legislation, which has become a major disincentive for landlords to rent their properties. National says it will restore the deductibility of mortgage interest for rentals, restore the two-year brightline test (from currently 10 years), and restore no-cause terminations. These measures should encourage many landlords to reconsider their decisions and make their properties available again for long-term rentals.

Rather than waiting for the next election or another study, the QLDC should urge the current Government to reverse these policies immediately.

Some private businesses, like NZ Ski, have purchased residential properties to house some of their staff. That is commendable. Other businesses should follow suit.

Some people have proposed that the QLDC should construct, or encourage the private sector to construct, temporary modular housing. In theory that could work, but is unlikely to create sufficient accommodation to make more than a small dent in the problem.

We may argue too that the Government should contract local motels to house our workers without accommodation, as it is doing in parts of the North Island, e.g. in Rotorua.

In the medium term, the Queenstown Lakes Community Housing Trust should expand substantially its stable of assisted housing to 1,000 or more within the next four years. For that, the trust would require substantial additional funding. It would purchase existing or new housing, or the land, and make them available to eligible low and medium-income households at reduced rents or ownership with restricted deeds, consistent with the trust’s assistance models.

A Queenstown Lakes Housing Trust success story, Frankton's Toru apartments have provided an affordable, secure home to dozens. Should the trust be backed to grow its portfolio?

The funds may be sourced and shared equally by the QLDC and the Government, supplemented by regional trusts, iwi, and other charitable sources. The QLDC may raise its share of the funds by issuing a dedicated 10-year bond, to be redeemed at maturity from our residential and commercial rates. The Government would add to the QLDC’s funding on a dollar-for-dollar basis by rebating some of our GST. The funds would be ring-fenced to be used specifically for the trust's assisted housing programmes.

Should property owners be concerned about underwriting a bond issue for this purpose, we must appreciate that Queenstown is an expensive place to live. Housing is especially expensive, with a median cost of housing-to-income ratio of 14 compared to a ratio of nine for New Zealand as a whole. Our professional and wage and salaried workers are integral to the social fabric, economic viability, and collective wellbeing of our community.

In the long term, the only way for our low and medium-wage earners to compete in the market place for scarce housing is to increase our productivity and wages. That means diversifying our economy away from mass tourism. Until the advent of Covid, our district’s median GDP (value added) per wage and salaried worker – the people who produce the goods and services in our economy - was running about 15 percent below the median for New Zealand. Our council should have pursued a diversification strategy long ago to facilitate our transformation to a higher-productivity economy. We should have learnt by now that more bums on seats doesn’t cut it.

It is pertinent to note, the consultancy Infometrics reported that in 2019, prior to Covid, tourism in the Queenstown Lakes District contributed 56 percent of the GDP of our economy. Employment increased by 5.6 percent over the prior year (2018) while the increase in productivity per filled job was only one percent. In 2022, following the major drop in tourism, the sector’s contribution to our economy fell by about half, to 25 percent. The number of jobs fell slightly and the productivity per filled job increased by – wait for it - 6.2 percent! These observations deserve further analysis, but they don’t bode well for our traditional tourism.

Final takeaways

Our district’s housing problem is real and serious. It deserves concerted and prompt action by the QLDC and central government – not more stalling or studies.

These proposals should be seen against the unprecedented pressures Queenstown is experiencing towards transformational change, from its traditional mass tourism model to an economy that is more productive, and where we value innovation and quality over quantity. The pressures are more of an opportunity than a threat. They predispose a reset. We all have a responsibility to share in the costs of living here, as we embrace our diversity and collective wellbeing - economically, socially, and environmentally.