Hope springs eternal for Lowburn's precious tap

Cromwell-based Crux senior journalist Kim Bowden documents her encounters with the legendary Lowburn tap - and how it could be a symbol of big regulatory changes in the pipeline.

It’s quite something, the Lowburn community tap.

In winter, a local wraps it in a scrap of woolen carpet secured by a bungy tie to stop it freezing.

In summer, there’s an almost constant flow of visitors to it, some obviously travellers passing through in caravans and people-movers converted for life on the road, others probably locals.

When I first moved to Lowburn, I had no potable water coming to my section, so I was a regular at the tap, filling two 20-litre plastic containers almost daily.

Rarely was there no-one to talk to.

Usually, there’d be someone before me, finishing filling up, or someone after me, next in line.

Some swore by the water for homebrew or sourdough starters; for others, it just made a fine cup of tea.

But, will the new Water Services Act spell the end of this beloved local institution?

(Left to right) Jackson Ieru, Harry Wobung, and Jacob Kintor are used to rainwater supplies back home in Vanuatu, and they're regulars at the Lowburn tap to fill up drink bottles after work.

James Maru and his crew have spent the day taking nets off grapevines, and they’ve come to the tap to fill drink bottles.

They come to Central Otago every year from Vanuatu, to jobs in vineyards and orchards.

It’s thirsty work.

“During the summer, we come almost every day, but during the winter, once a week.

“When it’s summer, it gets hot, so we drink a lot of water when we work.

“It tastes good, not like the water we use back where we live (in town).”

Regular refiller Young 'Whiskey' Song.

Young “Whiskey” Song has lived in Cromwell for 20 years.

He’s a twice-a-week visitor to the Lowburn tap.

Recycled plastic bottles are filled with water that his household uses for drinking and cooking.

“It’s very clean.”

Town water has “that white stuff” – he doesn’t know what it’s called, but it coats the inside of your kettle, he says.

Lindsay Warburton says that white stuff ruins the last mouthful of a cup of tea.

"There's nothing worse than having a cup of tea and having that gritty calcium at the end."

Cromwell's Lindsay Warburton says Lowburn tap water makes a good cup of tea.

He pops out to Lowburn regularly, filling old two-litre juice containers with water.

Nofo Lafita's the same.

He’s been a Cromwell local for seven years, long enough to learn to scrub out his jug a few times a week to stop the limescale.

He's at the tap once a week, sometimes once a fortnight, to stock up on water he reserves for drinking, and for making tea and coffee.

“The water, the quality of the water, is better than the tap water.

“You can tell the difference between it, you know, the one you get from here and the tap water.”

Kim Murtagh's next in line. She travels from Alexandra to restock her drinking water supply at Lowburn.

Then there’s Kim Murtagh, although most people call her “Dusty”.

She’s been making the Lowburn tap pilgrimage from Alexandra, where she lives in her van.

“I come here because the Alexandra water is disgusting...Honestly, you can’t drink the Alexandra water. It’s yuck.”

She's been a regular refiller at Lowburn since 2016, when she moved to Alexandra, she says.

“I love this water. I mean, I’ve filled up here previously, just travelling, because it’s beautiful water.

“To treat it would just be a crime, it really would.”

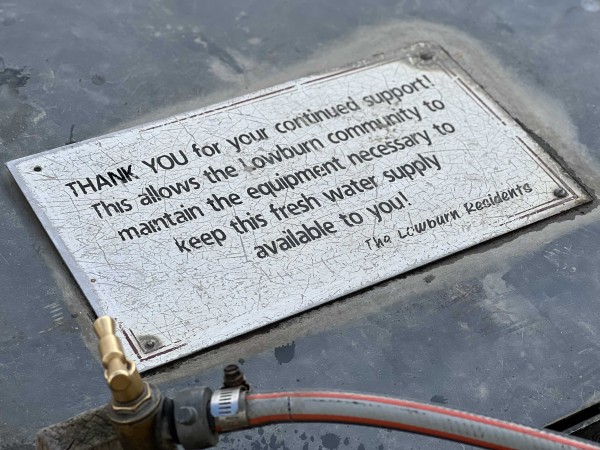

There’s a sign beside the tap, telling people it's maintained by the Lowburn residents, and there’s a pipe with a slot to take money at the top.

Dusty says she always puts money in it.

“Because it’s a community thing, and I believe in community."

Will the community custodians of the Lowburn tap keep it open as the regulatory burdern of doing so steps up?

Cromwell-based lawyer Bonnie Zareh, a director at Southern Peak Law, has had a read-through of the Water Services Act for Crux.

She says there’s no doubt the Lowburn tap falls under the scope of the new legislation.

It’s there in black and white: Clause 13(b) lists community water taps as a “point of supply”.

Decisionmakers have actively contemplated the inclusion of facilities like the one at Lowburn as they’ve developed the legal framework, she says.

Cromwell lawyer Bonnie Zareh says the Lowburn residents looking after the community tap have an increased legal burden because of new drinking water legislation.

So what does the Act mean for the Lowburn tap?

For now, those who operate it, knowing people treat it as a potable water supply, have an obligation to ensure they’re providing safe drinking water - that’s the overarching purpose of the Act.

If for any reason they weren’t providing safe drinking water, they could be found to be liable, including personal liability.

“Obviously, that’s quite a heavy burden on suppliers, particularly community groups,” Ms Zareh says.

The Act’s having a soft opening of sorts, with stiffer compliance obligations set to come into force over time.

By November 2025, the Lowburn tap and others like it will need to be registered and by November 2028, among various other requirements, have a comprehensive safety plan or have adopted an “acceptable solution” that demonstrates that they can comply with the Act.

At a minimum, it has been indicated a draft “acceptable solution” is UV filtration, for which the bill for installation and ongoing maintenance could run into the thousands of dollars.

There is also the option to investigate an "exemption" process, but exemptions will be difficult to obtain, she says.

The Water Services Act came into force in November, and is part of the Three Waters Reforms.

It has created extensive requirements and duties of anyone classified as a drinking water supplier under the Act.

Previously, only larger scale water suppliers were captured, under health regulations.

It's a huge shift, for rural communities particularly, with plenty still scratching their heads wondering what exactly they need to do to toe the legal line.

The Lowburn Hall, which the community tap sits outside, is owned by the Lowburn Hall Society, a group of local residents, who manage the hall and look after the grounds.

They acquired the facility from the Central Otago District Council in 2018 for $1, and they pay $1 a year to lease the land it sits on.

The group also holds a permit from the Otago Regional Council to extract up to 30,000 litres of groundwater per day, some of which is what pours out of the community tap.

Main image: Nofo Lafita says water from the Lowburn tap tops Cromwell's town supply for drinking and making tea and coffee.